Disclosure: Our content isn't financial advice. Do your due diligence and speak to your financial advisor before making any investment decision. We may earn money from products reviewed. (Learn more)

Few doubt that billionaire Warren Buffett is a smart man and a savvy investor. But he is also a hypocrite when it comes to the subject of hedge fund investing.

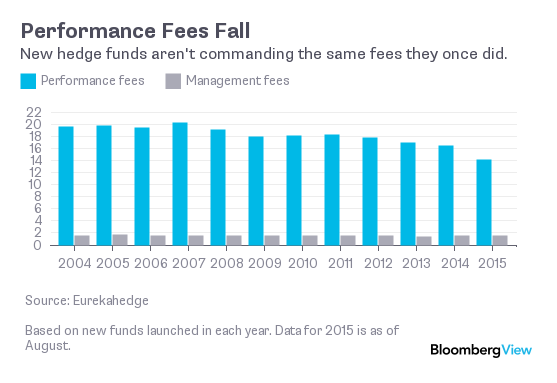

At the Fortune-sponsored Most Powerful Women Summit in October, he criticized the hedge fund industry, most notably its compensation structure; managers typically receive a management fee and a share of the profits. In essence, he argued that investors don’t get what they pay for, and that the emphasis is on marketing rather than returns. According to Business Insider, Buffett said “a lot of money out there [is] willing to pay high fees for the promise of performance. [You] don’t have to particularly deliver. [The] promise lasts long enough to get you and your children rich.”

One thing he didn’t discuss, however, was the fact that he has engaged in some of the activities he now criticizes. As investor Dan Loeb, the founder of Third Point LLC, a hedge fund with nearly $20 billion of assets under management, suggested at the SkyBridge Alternatives (SALT) Conference last May, Mr. Buffet’s attacks seem somewhat disingenuous:

“I love reading Warren Buffett’s letters,” Loeb said. “I love contrasting his words with his actions … I love his wisdom. He’s a very wise guy. But I also love how he criticizes hedge funds, yet he really had the first hedge fund. He criticizes activists, yet he was the first activist. He criticizes financial-services companies, yet he invests in them. He thinks we should all pay more taxes, but he loves avoiding them himself.”

Mr. Buffett isn’t the only one who has railed against “exorbitant” fees. In a March New York Times article, “A Mystery in Hedge Fund Investing,” financial planner Carl Richards argued that the associated expenses are “insane.” In October, the co-founder and CEO of a service for do-it-yourself investors said that “throwing money” at such “schemes” was “just dumb.” And earlier this month, the chief executive of a wealth management firm wrote in a Financial Times commentary, “There Are Too Many Hedge Fund Billionaires,” that such funds are “overly complex and overly expensive.”

Conflicts of interest

Unfortunately, as with the famous billionaire investor, at least some of those who slam the industry have what some might consider conflicts of interest. Many opponents are either associated with firms that compete with hedge funds for a share of the investment pie, or they are marketing products and services that will reward them with profits of their own if investors forego alternative investing in favor of other options.

Needless to say, the fact that the U.S. presidential election season is upon us also means that the hedge fund industry, which oversees trillions of dollars and which, admittedly, has a disproportionate share of wealthy participants, is a tempting target for politicians seeking to score populist points before the polls open. As with the pharmaceutical industry, which is being vilified for its success in creating and marketing products that people apparently need or want, the sector’s good fortunes have placed it in the political cross hairs.

Some might view it as ironic, of course, that those who profit from trying to make investors’ money grow are seen as taking advantage of those who use their services. Does anybody make the same arguments regarding the healthy profits that Apple makes on every iPhone, or that BMW realizes on every vehicle? Do people question whether they are handing over too much profit to McDonald’s for every Big Mac they eat? Of course not. It generally doesn’t matter how much a business earns on what it sells; what matters is the overall cost and whether it represents good value.

Does big equal “bad”?

Moreover, the argument that the industry emphasizes asset growth over performance is also somewhat specious. There’s no doubt that the bigger a hedge fund gets, the more it collects in fees. But that relationship generally holds true for nearly all investment products. Can it really be said that such incentives don’t apply in the case of a passively-managed index fund? Based on that argument, one might also argue that Apple is ripping us off by trying to sell millions of the same model of iPhone when it could be spending more time and money making better products?

Whether or not the level of fees is important doesn’t mean they are irrelevant. They are simply one facet of an investor’s overall return. What matters is the amount of money that investors have in their accounts after it’s been invested. As in other areas of life, if a service provider fails to deliver, then it makes sense to go elsewhere. Decades ago, U.S. car buyers decided to stop paying high prices for the shoddy products being made in Detroit, opting instead for better-made foreign counterparts. Domestic automakers were forced to improve if they wanted to stay in business.

Arguably, if overall hedge fund performance was as good as it once was, there wouldn’t be so much focus on the fees involved. In fact, many investors would probably be thanking their lucky stars for their investments. That said, it’s clear that the industry has become crowded with me-too and mediocre managers who don’t seem worth their salt. But is this any different than what one might witness in any other industry? If there’s money to be made, it naturally attracts plenty of competition, both good and bad. Ultimately, investors will have to vote with their feet and ensure that only the best remain.