Disclosure: Our content isn't financial advice. Do your due diligence and speak to your financial advisor before making any investment decision. We may earn money from products reviewed. (Learn more)

Many commentators have voiced opinions about what is wrong with hedge fund investing. In “The Misguided Focus on Hedge Fund Fees,” for example, I discussed widespread criticisms of the fees charged by managers. But complaints about performance have been just as prominent.

Lagging returns

There’s no question that the hedge fund industry is experiencing a rough patch. Although performance picked up in October, according to hedge-fund data tracker Hedge Fund Research, Inc., the firm’s Fund Weighted Composite Index, a global, equal-weighted index of over 2,000 single-manager funds, is virtually flat for 2015. In the prior two years, the FWCI rose 3.3% and 9.1%, respectively, while the aggregate hedge fund return for the decade through 2014 was 5.1%.

Not surprisingly, poor performance has been exhibit number one for those who say that hedge fund investing is a fool’s game. Questions like, “Why should I pay managers who can’t even keep up with the S&P 500?” or, “Why bother investing in funds that lack a consistent edge?” are hard to ignore. Aside from reflecting recency and other biases, the issue is not why hedge funds have lagged; it is the fact that, in most cases, an active approach has lagged a passive- or buy-and-hold–approach for many years.

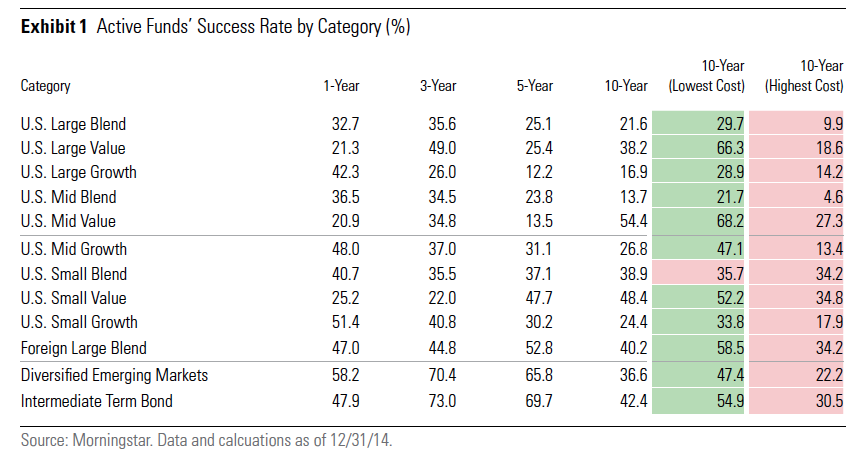

A case in point: according to a study by investment-research firm Morningstar, detailed in the Washington Post, actively managed mutual funds “lost out to their passive peers in nearly every asset class during the 10 years between 2004 and 2014.” On its face, this seems like a pretty strong argument in favor of low-cost, hands-off style investing. But as in many areas of life, such data needs to be viewed in a proper context.

Anything but normal

For one thing, market conditions over the past decade have been anything but normal. In the wake of the global financial crisis, which called the survival of numerous institutions into question, many were loathe to stick with perspectives that had been of little use during the era’s darkest days. Among other things, a strong desire to preserve capital spawned a dramatic and far-reaching preference for investments considered “safe,” seemingly regardless of cost. Paradoxically, it also fostered a mindset based on short-term thinking, rather than long-term planning, discouraging companies and investors alike from thinking about “business as usual.”

In the years since then, markets have been subjected to extraordinary interventions by various authorities, which have distorted various market relationships. Many investors have felt compelled to chase returns, follow the herd, and invest based on expected policy decisions rather than traditional corporate and economic fundamentals. Along with the widespread belief that the Federal Reserve has been targeting higher equity prices in a bid to kick-start the economy via the “wealth effect,” these and other crosscurrents have created an environment in which many savvy investors have faltered.

Indeed, it’s one thing to see markets being temporarily unsettled by short-term dislocations, with the understanding that things will eventually return to normal. It’s quite another to operate within a setting where interest rates, for example, have remained near multi-century lows for more than half a decade, creating a framework that is hard for anyone to understand, let alone take advantage of.

Sour grapes or historical reality?

For those who accepted the Fed’s machinations at face value and went along with owning risky investments at historically rich prices because that is what policymakers wanted, such arguments probably sound like sour grapes. Perhaps. But if history tells us anything, it’s that things change. Anybody who is wagering that today’s rising stars and persistent trends will be tomorrow’s is, by definition, making a high-risk bet. Arguably, that is exactly what those who favor passive investing seem to be doing.

This seems especially true if the Fed’s easy money regime is coming to an end, as a growing number of investors and analysts seem to think following the release earlier this month of U.S. employment data for October. Still, whether or not the central bank moves toward policy “normalization” in December, odds are that the investing environment will require a lot more nimbleness going forward than just “going with the flow.”

Of course, there are no guarantees that hedge funds–or other active managers, for that matter–will be better able to cope with changing circumstances than less sophisticated investors. Among other things, as Howard Marks, the billionaire founder of Los-Angeles-based Oaktree Capital, has noted, the pool of talent is probably less than it seems:

“The one thing I know is that 40 years ago all hedge funds were run by geniuses, and there [were not many of them]. Today I am sure there are not 10,000 geniuses.

That said, some of the greatest gains in history have come about from investing in areas that were hated or out-of-favor. While it would be hard to argue that hedge fund investing falls squarely in this camp–especially given that the sector continues to see steady inflows from institutional investors–when compared to index investing, it seems like a contrarian’s dream.